In this article, I am inspired to provoke our understanding (or misunderstanding) of the idea of sustainability. The inspiration comes especially from various discussions, social experiments, and observations when it comes to understanding and doing sustainability, especially those that are by nature cross-cultural. Being cross-culturally aware means being aware of the socio-cultural processes of how we have come to practice something or believe in what we believe and value what we value, including the biases that have developed over the course of our lives, in relation to ourselves and others and our relationships as well as potential conflicts.

In this article, I am inspired to provoke our understanding (or misunderstanding) of the idea of sustainability. The inspiration comes especially from various discussions, social experiments, and observations when it comes to understanding and doing sustainability, especially those that are by nature cross-cultural. Being cross-culturally aware means being aware of the socio-cultural processes of how we have come to practice something or believe in what we believe and value what we value, including the biases that have developed over the course of our lives, in relation to ourselves and others and our relationships as well as potential conflicts.

I attempt to connect many dots I can think of and at the end leave the readers with questions (of their own or of any kind), not answers. My thesis is that the notion of sustainability is a romanticized idea whose meaning remains dependent on who deals with it. Its resonance depends on socio-economic-cultural backgrounds of people. I shall present some evidence below. Nevertheless, this short article is not meant to be comprehensive.

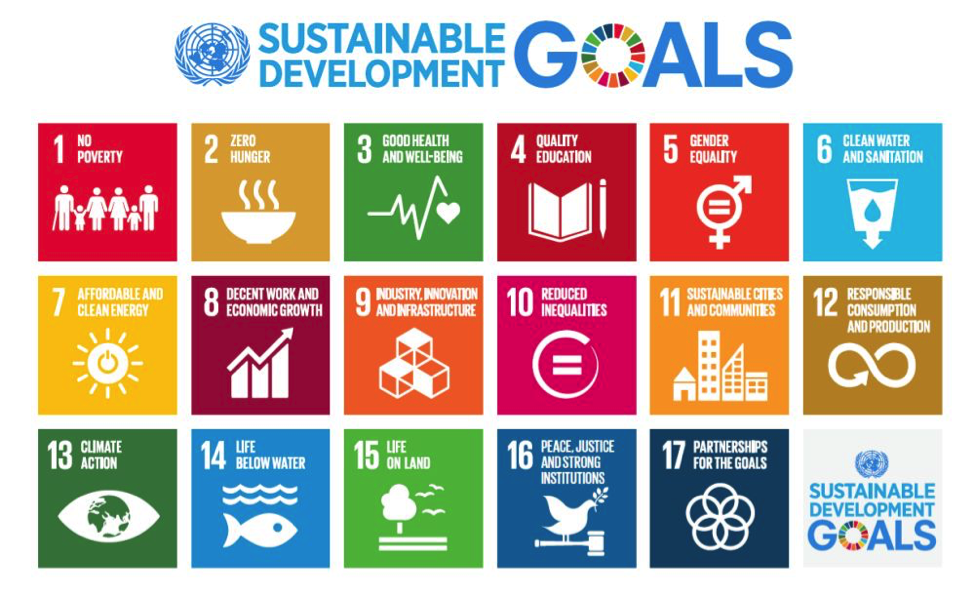

From a discussion with some sustainability experts (in separate talks) from ETH Zurich, when we met in Zurich for a class on cross-cultural and conflict management, it became clear that the way people understand and approach the idea of ‘sustainability’ is different. When teaching a class on sustainability, for example, one professor would know whether certain viewpoints came from students of management or from students of natural and social sciences. Generally, they would have different concerns and interests, and specific ways of looking and projecting their thoughts. Education backgrounds present certain subjective cosmologies that detail how the world looks like and should look like. These are essentially cultural. Dealing with both Swiss and Indonesian counterparts, another professor would occasionally find disparity in the way he and these stakeholder groups and partners had in mind and practice when it came to sustainability. There were different expectations and standards. These are also essentially cultural. The notion of sustainability remains an abstract idea that is understood differently by different groups and individuals.

During one of my classes on cross-cultural and conflict management at the MBA Program in Bandung, I assigned students to do a role play in relation to the idea of sustainability. Students had to gather information about sustainability beforehand and integrated that to a role they played, with a specific national and industry background. What became part of our discussions was the fact that they had different ideas of what sustainability entailed and this was part of the ‘conflict’ that they had to pass through. They have lived in different worlds. Sustainability can mean something related to doing corporate social responsibility to some students but it may also entail something that a business entity does (or should do) in order to sustain itself or survive. Even ‘corporate social responsibility’ is philosophically and practically different across different institutional and cultural settings, as argued by Matton and Moon (2008). What was clear was that no one could claim a monopoly over a definition.

So, how does understanding the fact that we may understand the idea of sustainability differently impact our daily practice as a human being or a business person? I argue that it is important to unravel our assumptions about human relationship with nature, along with the power that governs natural and human entities that in English is called “God” One subjective assumption speaks about humans being superior to nature, while the other subjective assumption speaks about nature being superior to humans. For the former, the implication is that humans are driven towards either exploiting and changing nature or taking an active participation in preserving nature. For the latter, the implication is that humans are driven towards accepting nature as it is or taking a rather passive-submissive role in nature. What is perceived as a “bad” condition is not necessarily bad. In both assumptions, there is a likelihood that humans make something either constructive or destructive.

It has become a major argument that industrialization has led to destructions towards humanity and of nature. The exploitation mindset has prompted backlashes from multiple stakeholder groups that demand more balanced, humanized, environmentally friendly practices. In a way, an exploiting and a manipulative action has been balanced by a more human-centered and nature-aware decision and action. The cultural mode has been the same: action. Indonesia, which can arguably be characterized by openness to many different foreign cultural influences, has begun to embrace this cultural mode of thinking – that action is necessary. So, initiatives taking place in more industrially advanced societies such as splitting trash bins or cans for different kinds for trashes have entered the mindset of many Indonesian people. This culture of splitting things into parts has been what science is based upon, splitting the world into different kinds of concepts different from other concepts. In essence, it is a way of thinking based on the understanding that each entity has its own characteristics. From one side, this can be a good thing. On the other hand, from a different angle, it can be seen as a copycat approach to decision making and culturally-unaware. Overall, sustainability from one (cultural) approach can be seen as the human approach to live the life as we know it longer or more sustainable by making sure that social and institutional arrangements are in place to secure the sustainable life for our generation and for the generations to come. It is cultural because it is what people (as a collective) believe where human practices go along with the belief or at least are directed towards satisfying the belief. All efforts are believed to require efficiency. People want change now by acting!

The second assumption about human-nature relationship will paint a completely different picture about how this notion of “sustainability” entails, philosophically or practically speaking. In contrast to the first assumption, humans believe that they are not superior to nature. Whatever life takes us, it is where it is best for us. Regardless of whether we suffer or not, whether we die the next day or not, it is life beyond what one can imagine. Everything, every fate, is believed to be already written. People from the first assumption believe that humans need to create their own fate, while people from the second assumption believe that fate makes humans. Therefore, efforts are not directed towards reducing the suffering through various rather tangible innovations and inventions but rather towards the acceptance of whatever “bad” things happening in the world. Practically speaking, when it comes to trash management in its broader sense of the word (not necessarily in a technical sense), people may depend on nature to regulate (or manage) the trash. This may be conscious or subconscious. Whatever is from the earth belongs to the earth and it will be up to the earth to process it. Efficiency is not an issue here as time is regarded as relative. Whether it takes long or short for the earth to regulate trash, it does not matter. Concerns about the length of time are usually a human business. Living on the earth is after all temporary. From this point of view, the idea of sustainability from does not emphasize human approach to make our life sustainable or longer. Nature has its own way to regulate itself beyond the capacity of any individual being.

Speaking of trash, different societies may have different conceptions and realities when it comes to understanding what trash is or what constitutes trash. The nature of trash is different.

From these two perspectives, conflicts are then very obvious. But this is, I think, the challenge of talking about sustainability because it addresses our implicit assumptions about how the world works and should work. Cross-cultural knowledge speaks about the multiple ways in which humans think across space and time. Sustainability is not an easy thing and we do not want our mind to be colonized. But one thing we know, the earth has survived for as long as it has been, with humans on it, coming and going. Whether we believe that it is partly based on human efforts or the work of nature to a greater extent is part of our conversation. It is not merely a philosophical debate as the belief has direct implications on what we humans create or attempt to create or let loose. Even if we are religiously or spiritually inclined individuals, we may perhaps have different answers, depending on how much and how deep we have been exposed to these ways of thinking-thus our biases in decision making. This is where the objective world we live in is understood subjectively. In addition, I wish that the perspectives laid out above are not seen as absolutes. Rather, they are meant to provoke and enable for a reflective turn.

And as I have mentioned above, I intend to leave the readers with questions. If we have all the answers in the world and if we agree on everything, we won’t perhaps have any conversation at all. If anything, many religious teachings point to the importance of seeking the middle path.

So, who gets to rule the world?

Author: Andika Putra Pratama

References for a Cross-Cultural Mind

Chen, Y. R., Leung, K., & Chen, C. C. (2009). 5 Bringing National Culture to the Table: Making a Difference with Cross?cultural Differences and Perspectives. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 217-249.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological review, 98(2), 224.